A type of marine snail could be used to create a fast-acting insulin to help type 1 diabetes, researchers have said.

A US team says that the insulin derived from the venom of cone sea snails has brought them one step closer to developing new medication.

This isn’t the first time cone snails have been investigated in diabetes research. In 2016, Melbourne researchers discovered a protein in the venom which could help experts develop ultra-fast-acting insulins for future treatment.

Now, the Utah researchers involved in this new study claim they understand more about the insulin produced in the snails.

“These snails have developed a strategy to hit and subdue their prey with up to 200 different compounds, one of which is insulin,” said senior author Helena Safavi-Hemami, assistant professor of Biochemistry at the University of Utah Health.

From studying three types of snail species – Conus geographus, C. tulipa and C. kinoshitai – the team found the insulin differed slightly in all the snails.

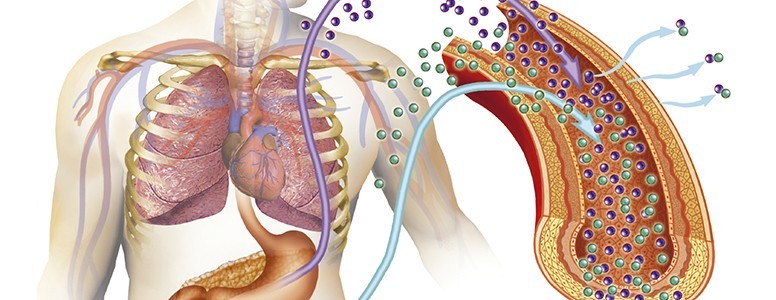

Insuli, which regulates blood glucose levels, is made up of two segments called A and B chains. It is the B cluster that allows the body to store the hormone for later and activates the insulin receptors which tell the body to take glucose from the blood.

Manufactured insulin currently contains the B chain because it is needed to kick-start the insulin receptors so they can lower blood glucose levels, but this process delays the hormone from working.

The snails studied all lacked the sticky part of the B chain. This means the snails produce a fast-acting insulin.

The study team tested the snails’ insulin on zebrafish and mice which had been given medication to induce type 1 diabetes symptoms. They found the snails’ insulins lowered the animals’ blood glucose effectively, but it was up to 20 times less potent than human insulin.

“We are beginning to uncover the secrets of cone snails,” said Safavi-Hemami. “We hope to use what we learn to find new approaches to treat diabetes.”

There are hundreds of different species of cone snail which are typically found in warm and tropical seas around the world. Now, the researchers plan to use each unique insulin configuration they discovered to analyse how new drugs can be created that act quickly and effectively.

The findings have been published in the journal eLife.

What's new on the forum? ⭐️

Get our free newsletters

Stay up to date with the latest news, research and breakthroughs.